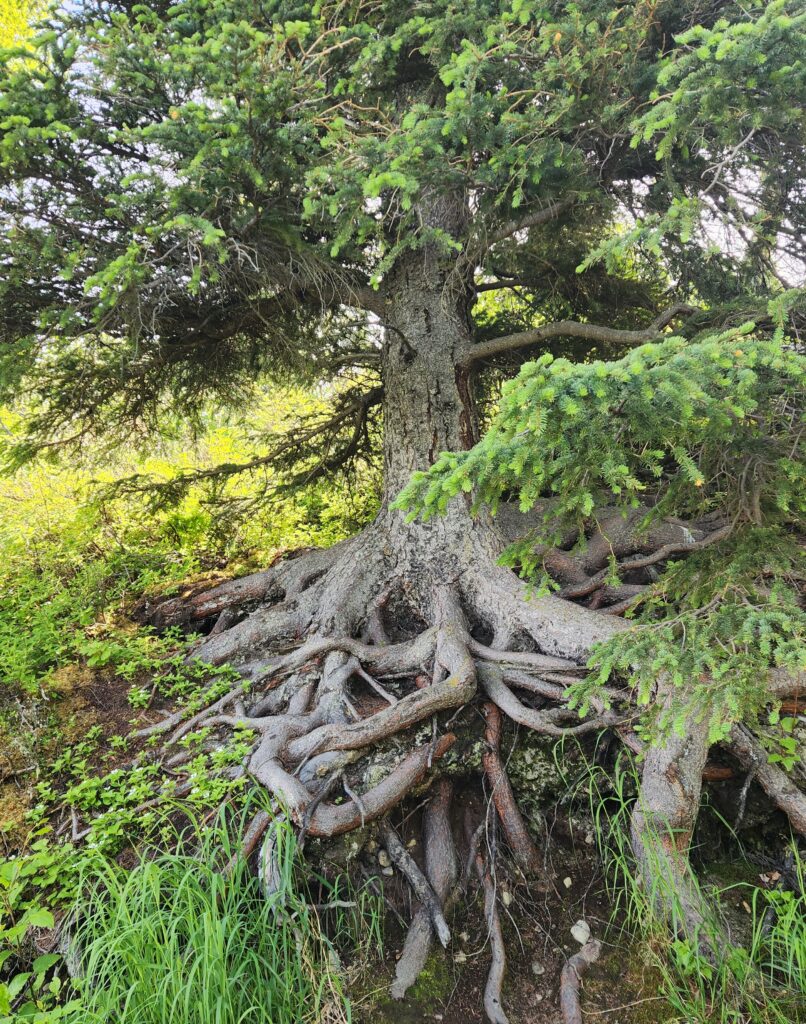

I must have passed this tree dozens of times over the years while hiking this trail in Chugach State Park. Maybe I’m walking a little slower these days, but today I pause to appreciate him—the bright new tips of his branches, the pockets of orange pollen set to scatter at the slightest breeze. His roots spread wide, not deep, in this thin mountain soil. Thick, rough, and twisted they reach down the slope toward the trail, and up into the hillside, mingling with other spruce, alder, fireweed, and grasses. He survived the spruce bark beetle devastation that killed most of the spruce trees in this part of Alaska a few years ago. Maybe this tree was too far up the mountain for the winged insects to reach him, or maybe on the spring day when the beetles popped out of their host trees the breeze swept them to other trees, or maybe this tree carries some intrinsic defense against them. Alaskan spruce may live to be 250 to 300 years old. Judging by his stature and girth, this tree is surely an elder.

On this warm June day, my husband Jim and I join other travelers on the trail—families, joggers, dog walkers, mountain bikers, tourists, old and young. We greet each other: “Great day, isn’t it?” or “Seen any animals?” Bears and moose have left their piles of scat as messages that they too own the trail and this half-million acres of wild land. We have the privilege of walking here today because fifty-four years ago an unlikely coalition of hikers, skiers, and back-country adventurers of all political persuasions banded together to convince the state of Alaska to convert what was once Forest Service land into Chugach State Park. They believed that this vast stretch of wild land should be accessible to all of us, not closed off by mining, denuded by logging, or blocked by private ownership.

Before this was a park, I roamed these mountains with my high school friends. We never imagined that we might be denied entrance to the land. Later, away at college when the park was dedicated, I did not appreciate the work of the people who convinced those in power to preserve it. But over the years, as my husband and I have shared the park with our daughter and grandchildren, we have tried to instill in them the respect for the land and our connection to all the creatures who share the park.

This tree got its start long before I was born, or my parents, grandparents or great-grandparents. Long before we settlers moved in, the Chugachmiut, for whom the park and mountains are named, and the Denaina people sustained themselves with the resources of this vast territory. Now that I’m an elder, whose life will certainly run out before the tree enters its final phase of sinking back to the land, I hope to learn something about resilience from him in these times of turmoil and climate upheaval—how to achieve stability by reaching out to those around me, and how to replenish the earth by nurturing others.